Mimmo Iacopino

Following the teaching of Dadaism, Iacopino’s works are made from elegant interweaving of unusual compositional elements, such as strips of velvet, satin ribbons or shiny lurex, multicolored moulin cotton threads, but also tailoring meters, fragments of musical scores and strips imprinted with phrases of literary texts.They’re all materials decontextualized from their field and their function that enter the dimension of art recomposed in geometric warps inspired by arithmetic modulations, where the construction of the grid is marked by mathematical measurements that sometimes dissolve, following mathematical rules of ordered madness. In this sense, Iacopino knows how to unite the Dadaist principle of the objet trouvé, of the surprise that the spectator feels in front of the materials used by the artist, to the great abstract and geometric season of 20th century art. Each of his works is characterized by the continuous expansion of the interweaving of geometric patterns with a three-dimensional and alienating effect, accentuated by the rhythm of chromatic repetition, hypnotic and enigmatic, where each element performs the function of a multiplied sign, thus involving the viewer in an ever-changing dialogue with the pictorial matter of his art.

In the works from the 2000s, thanks to the photographic skill in the digital processing of the natural image without using photomontages, colored pencils, ballpoint pens, matches and thermometers, are manipulated, intersected with each other in compositions marked by a modular geometric rhythm that will be, later, transferred to the canvas with the same procedure, but with the materials he’s best known for: velvet and satin ribbons and tailor’s meters, where the chaotic and surreal thought is rationalized through the interweaving of perpendicular lines, scanned with maniacal precision.

Works

-

Coordinate di allunaggio - Luna a colori (1969-2019)

Coordinate di allunaggio - Luna a colori (1969-2019)VELVET, SATIN, LUREX RIBBONS METERS FOR TAILORS BRAIDED ON CANVAS

-

You should be dancing

You should be dancingVELVET, SATIN, LUREX RIBBONS METERS FOR TAILORS BRAIDED ON CANVAS

-

Sottoriflessi

SottoriflessiVELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS AND SYNTHETIC MIRROR ON CANVAS

-

Sottoriflessi

SottoriflessiVELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS AND SYNTHETIC MIRROR ON CANVAS

-

Sottoriflessi

SottoriflessiVELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS AND SYNTHETIC MIRROR ON CANVAS

-

Amleto a colori

Amleto a coloriTEXT WRITTEN IN INDELIBLE INK JET ON SCRAPS OF CANVAS STRIPS AND SCRAPS OF VELVET AND SATIN EVERTED IN ROUND HOLES ON CANVAS

-

Metamorfosi

MetamorfosiVELVET STRIPS AND TAILOR METERS ON CANVAS

-

Metamorfosi

MetamorfosiTAILOR'S METERS AND VELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS WOVEN ON CANVAS

-

Sottopittura

SottopitturaWOVEN VELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS AND ACRYLIC PAINTS ON CANVAS

-

Double Metamorphosis

Double MetamorphosisWOVEN VELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS AND ACRYLIC PAINTS ON CANVAS

-

Colors Numbers

Colors NumbersVELVET STRIPS AND TAILOR METERS ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledVELVET STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Solstizio d’estate

Solstizio d’estateVELVET AND SATIN STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledVELVET AND SATIN RIBBONS WOVEN ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledVELVET AND SATIN STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Riunione a colori

Riunione a coloriVELVET AND SATIN STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Riunione a colori

Riunione a coloriVELVET AND SATIN STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Riunione a colori

Riunione a coloriVELVET AND SATIN STRIPES ON CANVAS

-

Onde sismiche

Onde sismicheBRAIDS OF COTTON SEWING THREADS ON CANVAS

-

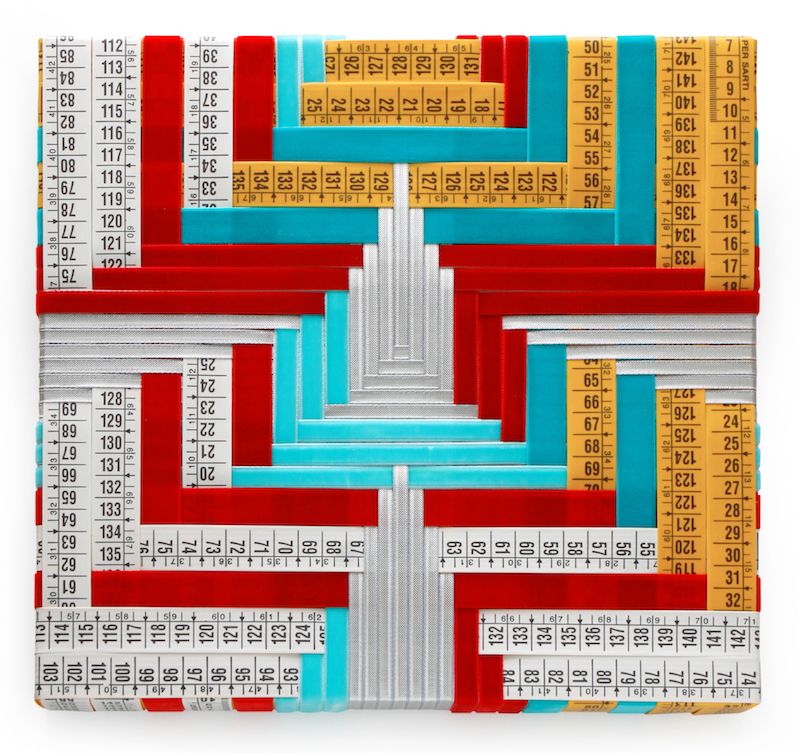

Untitled

UntitledTAILORS' METERS ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledTAILORS' METERS ON CANVAS

-

Cortocircuito

CortocircuitoCOPPER WIRES ON CANVAS

-

Onde

OndePOLYESTER THREADS RAT TAIL ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledADHESIVE METERS AND METALLIC COLOR

-

Divina per sempre

Divina per sempreSTRIPS OF PAPER AND INK ON CANVAS

-

Untitled

UntitledSCULPTURE OF METERS FOR TAILORS ON CARDBOARD BASE

-

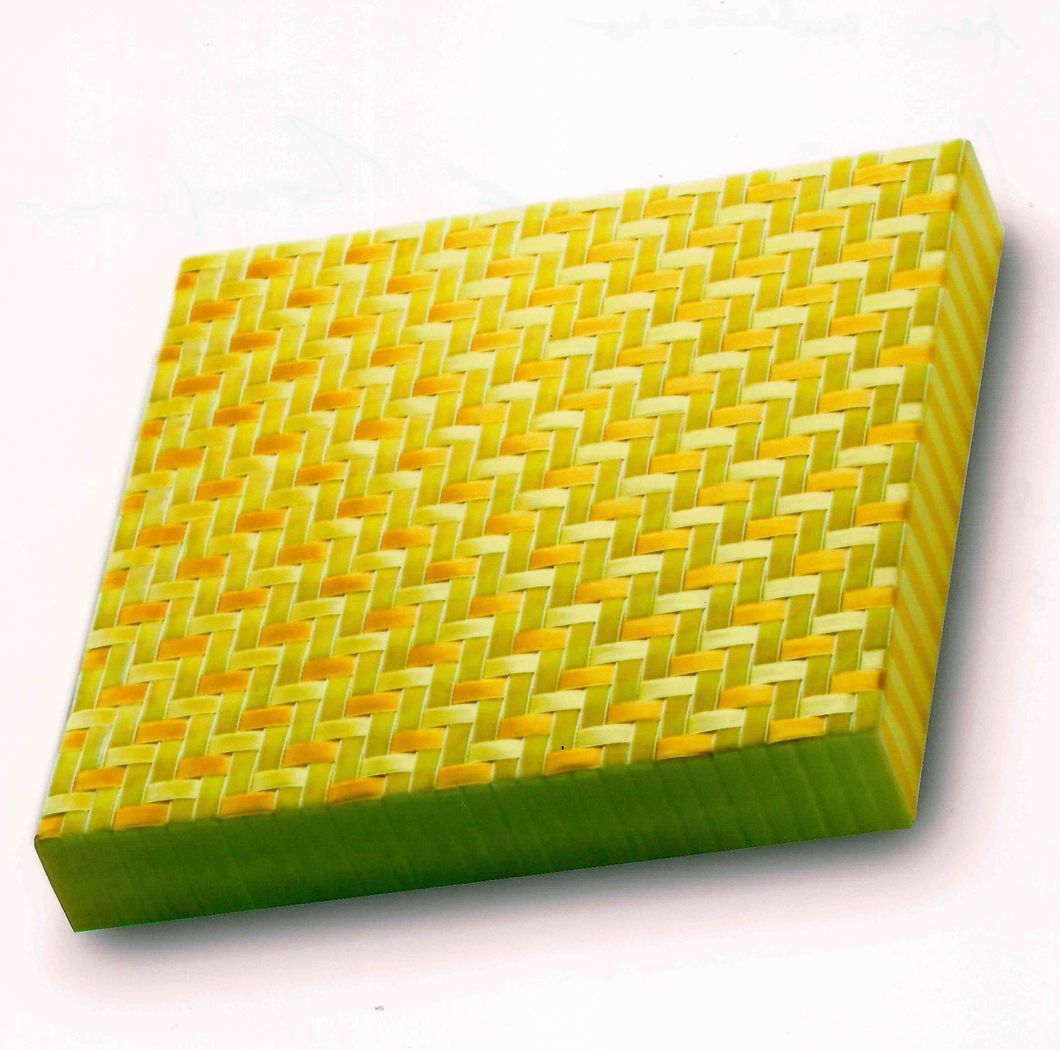

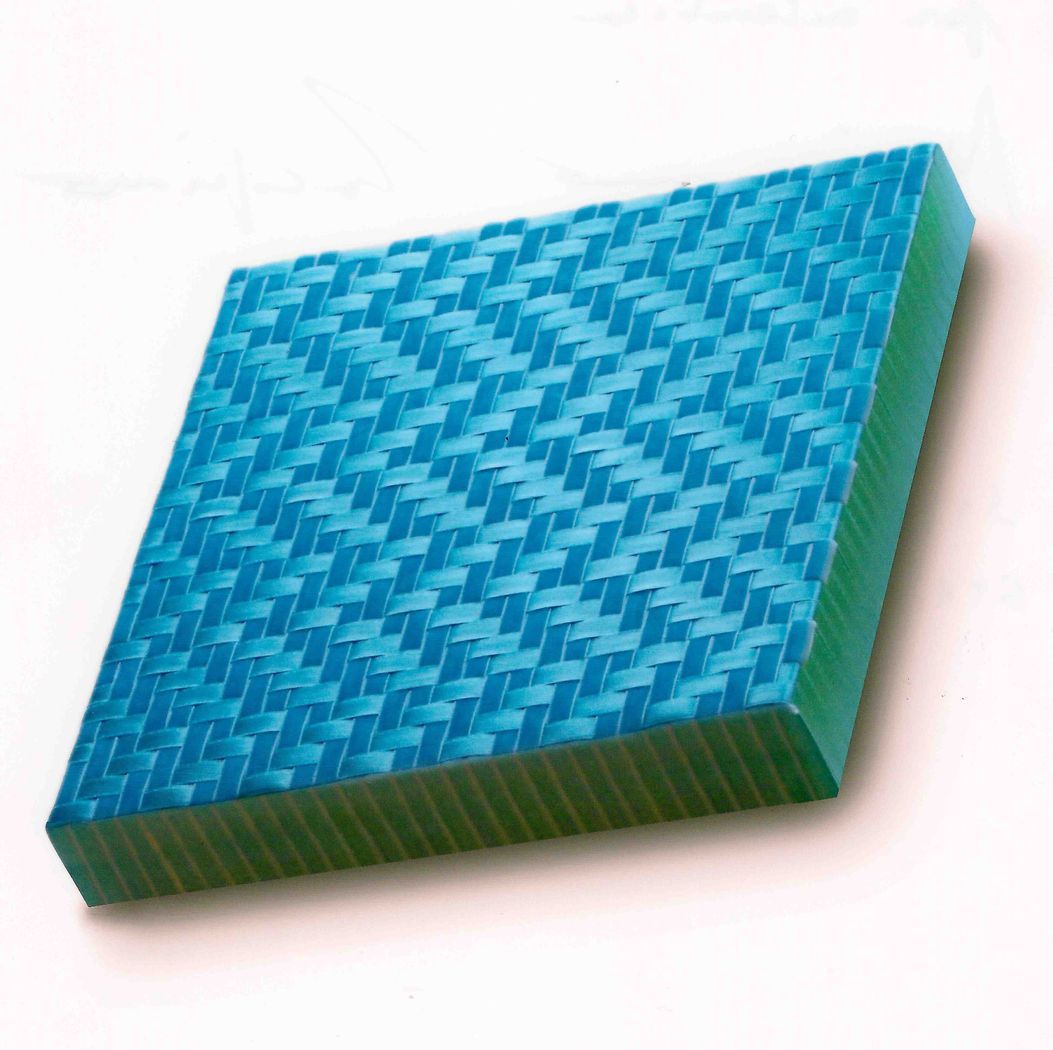

Untitled

UntitledSCULPTURE OF METERS FOR TAILORS ON CARDBOARD BASE

-

Misure mosse

Misure mosseVELVET, SATIN, LUREX RIBBONS METERS FOR TAILORS BRAIDED ON CANVAS

-